The home of the Seymours, Bailys and Evans

Many names are mentioned in this (very long) article. I would advise reading some of the other blog-posts relating to the Seymour, Baily and Turner family to understand better how they are linked.

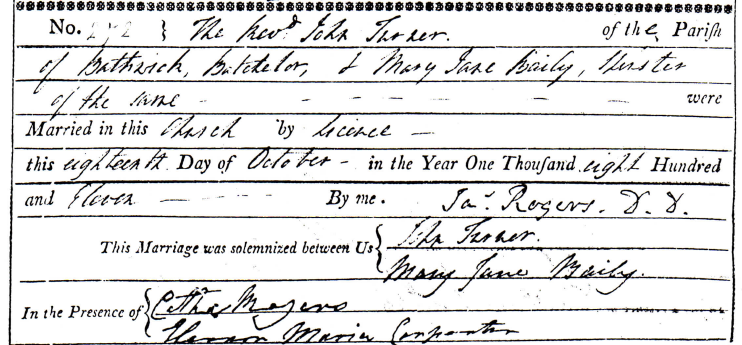

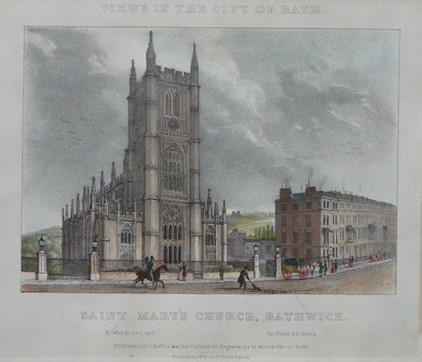

In July 1899, Commander Edward Seymour Evans, of Whiddon Park, Chagford, Devonshire, wrote to Charles Turner, a teacher near Horsham in rural Victoria, Australia. They were cousins, though they did not know each other. Commander Evans was concerned about what would happen to Whiddon Park after his death. He was the “heir in tail” of the property after their mutual great-uncle Edward Seymour Baily had left it to his niece, Mary Evans, nee Turner, and her children, for their use during their lifetime.

In his letter, Evans stated that “until lately I have never heard of my Uncle Andrew Turner’s family. You may be aware that this property [Whiddon Park] is entailed & that in due course providing neither my brother or self have issue, will descend to uncle Andrew’s eldest living representative.” He then enquired about his uncle Andrew’s eldest son, called John Bailey Turner, whose whereabouts he wanted.

The letter was also part warning: “My reason for writing is that I think whoever inherits it should be informed of the exact condition of affairs, and on hearing from you I will provide them, there is no doubt that Mr. Baily never wished the place to be sold, but the money he intended (in my opinion) to be left – with the possession of the property has been left elsewhere, and the place is a perfect ‘white elephant’ to anyone without a fair income to keep it up.”

This letter has always fascinated me. Did Charles Turner reply? Did Evans write to others in the family? As Whiddon Park very clearly did not end up in the hands of Andrew Turner’s family, nor any other Turner relatives, what happened to the house and its contents?

Another curiosity to me is that Charles Turner’s father, Andrew Cheape Turner, was not actually the next male in the lineage. Andrew was the youngest son of his parents, the Reverend John Turner and Mary Jane Baily. His older brother Alfred Rooke Turner (my great-great grandfather) had sons. So why were Andrew’s family mentioned as next in line instead of Alfred?

After many years of research, I have found answers to some – but not all – of my questions.

Whiddon Park

Whiddon Park is situated in the Devonshire market town of Chagford, on the edge of Dartmoor, and in the valley of the Teign river. The property, originally consisting of about 300 acres, was named for the Whyddon family, who owned it from around 1570.[1] Some say the house was built by Sir John Whiddon, who died in 1575, but there is a plaque above the door reading “1649,” indicating that’s when it was built, in which case it was probably built by Rowland Whyddon.[2]

I visited Whiddon House in the mid-1990s. I was not able to look inside, nor go around the back, but the owners at the time allowed me to take a few photos. Looking at it from the front, Whiddon House is pleasant-looking large square house made of granite stone. It is also oddly situated, enclosed on two sides by steep slopes.

A 1988 survey by the National Trust described it as built in an L-shape, and three stories tall, with 9 chimneys. The Ground Floor had 2 dining rooms, 2 sitting rooms, 2 kitchens, a stair turret, back lobby, and lavatory. The First Floor had 5 bedrooms, 2 Bathrooms, and one Lavatory. On the Second Floor there was a Playroom, 3 further bedrooms, a store-room, a study, a box room, 2 bathrooms, and a Lavatory. Inside it had dark oak panelling, large granite fireplaces, mullion windows, and decorative plasterwork.[3]

A deer park was created in the Tudor era by Sir John Whiddon (circa 1570)[4], which covered 195 acres[5], enclosed by a high wall made from immense blocks of granite. “The park is wonderfully picturesque, with granite outcrops, groves of ancient oak, ash, and rowan, broom, gorse, bracken and bilberry, and a lichen and invertebrate community that has survived from pre-Neolithic woodland.” [6] A visitor in 1793 called it “a truly romantic spot,” and said that “behind the house, we are presented, at a little distance, with a distinct view of rock and wood, the most beautiful I have observed in the vicinity of the Teign.”[7] Today, the deer park is owned and managed by the National Trust, and there is no public access to the actual woods, in order to preserve the plant and wildlife.

In 1851, in his handbook for travellers, J. Murray was glowing in his praise for Whiddon Park: “No stranger to this neighbourhood should neglect to visit Whyddon Park, a romantic hill-side at the entrance to the gorse of the Teign, and a short 2m walk from Chagford by a path along the river bank. You will enter the park at the mansion of Whyddon, anciently the seat of the Whyddon family, and now the Bayleys. Here are huge old Scotch and Silver firs to delight you at the threshold; but higher on the hill are scenes and objects magnificently wild, – vistas of beech and aged oaks, chaotic clatters and piles of granite, herds of deer among the ferns and mossy stones, at a distance, the towering tors of Dartmoor.”[8]

From the Whiddons to the Northmores to the Seymours

The Northmores came to possess Whiddon Park, probably through a marriage with the Whyddons.[9] By the early 18th century, William Northmore of Cleve owned it. Northmore was an inveterate gambler, and lost £17,000 in one sitting, on the turn of an ace of diamonds in a card game called putt.[10] The modern-day value of this bet is probably close to £2 million.[11] Whether or not this particular loss led to his financial straits, William Northmore obtained mortgages on a number of his properties. Henry Portman, of Orchard Portman, was one of the men who loaned him money. Portman loaned him over £20,000, with the security being a long list of properties, mainly in Devonshire.

When Portman died, his great-nephew Francis Seymour inherited his vast estates and personal property, including the debt owed by William Northmore, which had not been fully settled in either Northmore’s or Portman’s lifetimes.

When Francis Seymour died in 1761, that same debt owed to Portman by Northmore had still not been fully settled, and was passed down to Seymour’s heirs. The bulk of the real estate went to Francis’ son, Henry Seymour. Henry took it on himself to do something about the Northmore debt, and instituted a number of successful Chancery Court cases to recover it.

Whiddon Park and the Bailys

Portman’s Will had made it clear that the estates were to be entailed on the male line. A controversy arose relating to a Codicil to Francis Seymour’s Will, which is detailed <here>. In summary, the codicil named his daughter Mary, the wife of John Baily, as the heir to her father’s property. However, her brother objected, and took the matter to Chancery Court. The end result was that Henry inherited most of the real estate, but some of the Devonshire properties previously belonging to Notrhmore were settled on Mary Baily.

Married women in those days did not have sole rights to their property. Upon marriage, husband and wife became “one person” under English property laws, and a married woman’s ability to own property on her own ceased to exist. Any property acquired by a wife (such as through inheritance) – unless specified to be for her own separate use – came under the control of her husband. Married women could also not dispose of their property nor write a Will without her husband’s consent.[12]

Family lore has it that John Baily spent his wife’s inheritance, and had to sell off some of the properties to pay his debts. However, Whiddon was not sold. It appears that John Baily did live at Whiddon in the year or so before his death, but I do not know if Mary ever did. John is buried at Chagford, but Mary is not, and they died within a year of each other.

No clues are to be had from Mary’s Will, as it was written and signed in 1774 while they were living in Ramridge house, in Weyhill, Hampshire, and before the Chancery suit relating to her father’s Will and Codicil had been fully settled. The construction of her Will reflects this. She mentions the contingencies should property be settled in her favour, or not. If it were, then her eldest son would inherit the properties. Whiddon is not specifically mentioned.

In his Will, John Baily left his Manor of Dunkeswell in Devonshire, and “all other my Messuages Tenements Lands and premises whatsoever or wheresoever situate” as well as his personal estate, to his “well beloved son” Edward Seymour Baily. Again, Whiddon is not specifically mentioned. Several properties in the parish of Dunkeswell were part of the Northmore properties settled on Mary Baily, and I’m presuming Whiddon fell into the category “all other” properties.

The next person to live at Whiddon Park was Edward Seymour Baily, eldest child of John Baily and Mary Seymour. Edward was born in 1761, a few months before his grandfather Francis Seymour died. ES Baily served in the navy, retiring with the rank of Captain. He did certainly live at Whiddon Park, as is mentioned in numerous letters between the Bailys and their lawyers.[13]

Captain Edward Seymour Baily married Phillis Rooke on the 9 Oct 1790 at Wells St Cuthbert. Per their marriage settlement drawn up between them just days before they married, Captain Baily conveyed Whiddon Park into the hands of Trustees, who would then manage the income derived from the property. After Mr and Mrs Baily died, the Trustees were instructed that their property would be settled equally between any children they would have. They went on to have two children, Mary and Edward.

The Bailys faced financial difficulties, and it is presumed that they no longer held any of the other property inherited by Edward’s mother, as correspondence from their lawyers stated that Captain Baily had no other assets or source of income besides Whiddon. After his wife’s death in early 1832, Captain Baily decided to settle Whiddon Park on his son Edward. Judging from the attorneys’ correspondence, this was not a simple matter. There were questions as to whether the Title to Whiddon was sound and sufficiently comprehensive. Furthermore, the property was subject to a mortgage debt of £1706. In addition, according to the terms of the marriage settlement between Captain and Mrs Baily, if Whiddon was to be settled on Edward, then something had to be settled on his sister, Mrs Mary Turner. Another piece of land, described as a “nominal part” of the estate – a field called “Honeybags” adjoining Whiddon Park – was to be settled on Mrs Turner.[14] One can see that this was not equivalent to being left Whiddon Park, including the house, which no doubt would have been useful for the Turners’ growing family (they ended up having 10 children). According to their lawyers, “Mr & Mrs Turner are very indignant at the intended appointment, & therefore most certainly will not join as they have expressed their intention of using their utmost exertions to prevent the appointment.”[15] Note that Rev. Turner believed the whole of Whiddon was worth at the time £6,000. I doubt the field was worth anything close to that sum.

Regardless of Mr and Mrs Turner’s objections, the plan proceeded. The plan was executed in the early 1830s, and Edward Seymour Baily junior came into possession of Whiddon Park. Captain Baily would pay a nominal rent to his son, and continue to live in the house.

Who lived in the house form 1840?

Captain Baily died in 1840, and is buried in the churchyard at Chagford. It seems particularly galling to me (as a descendant of the Turners), that it appears that his son Edward Seymour Baily did not live at Whiddon after his father’s death. Certainly in the 1841 census, there is no entry for Whiddon House in the returns for Chagford, although there is an entry for a farming family by the surname of Webber at “Whiddon.” The likelihood is that their residence was actually “Whiddon Farm. A probate notice in the Exeter Flying Post relating to the Estate of Mary Ponsford Webber makes this clear.[16]

At least Edward did the decent thing by his sister after the death of her husband Rev. John Turner in 1846. Mary and her daughters went to live at Whiddon House for a few years. They were at Whiddon on census night in 1851. By the later 1850s, Mary Turner and her children had left Whiddon. The children were grown up by then, and had gone their separate ways. Mrs Turner spent quite a few years taking turns living with her settled children, particularly Henry in Ireland and Mrs Mary Evans in Surrey. She died in 1876 in Strathpeffer, Scotland, where she had lived for a few years.

Meanwhile, Edward went to live in Reading, Berkshire from at least the 1860s onwards. Per the 1861 census, he was a visitor at 21 Sydney Terrace, Reading, Berkshire, the home of his cousins Ann and Emelia Michell. Curiously, he was also there in 1871, where he is described as “Head cous”, although he is only there with two servants. Perhaps it was the Michell’s home, but they were absent. Finally in 1881, Edward Seymour Baily resided at 67 Castle Crescent in Reading, Berkshire, where he lived until he died. It may be that he rented out Whiddon Park because the income received from this would enable him to live a more comfortable life elsewhere. It may also have been too large a place for a bachelor.

Edward Seymour Baily’s Will

When it came time to write his last Will, signed on the 4 Mar 1879, Edward favoured his niece Mary Jane Evans, even though he had nephews alive. In some ways, this is not surprising. He was geographically close to Mrs Evans and her children, and there are many indications of their friendly relations. Meanwhile, his nephews were scattered across the world (Ireland, Canada, South Africa and Australia).

He devised his property (including Whiddon) to the use of his niece, Mary Jane Baily Evans for her life, and after her death to the use of her eldest son George Bruce Evans for his life, then to his sons successively in order “in tail male”; and if George had no sons, then to his daughters. If George had no children, or they died without issue, the entail then went to Mary’s next son, and so on. Mary’s daughter Mary Emily Evans and her issue were then last in this line.

If none of the Evans had issue, then the estate was to go to Edward Baily’s “right heirs”. In this context, the next in line would be his eldest living nephew, and then that nephew’s issue, with preference given to their sons first, and then on to the next nephew, and the next, etc.

The Evans

ES Baily died 15 Feb 1886. His niece Mary Jane Baily Evans, the wife of Captain John Evans, proved his Will. She had possession of Whiddon for only a few years before she died on 9 Jul 1893, but did not ever live there. In the meantime, her eldest son George Bruce Evans had died, on the 15 Mar 1886, without issue. Next in line was her son Edward Seymour Evans, who became the tenant-for-life of Whiddon Park, and receiver of its rents and profits.

When he wrote to Charles Turner in 1899, ES Evans was 55 years old, and still a bachelor. His elder sister Mary and two older brothers (John and George) had died unmarried. His younger brother William Hunter Evans was the only sibling left. While Hunter had been married, there were no children of the marriage. By this time, it was clear to ES Evans that neither he nor his brother were likely to have children, and he’d better do something to determine who was the next heir.

His two youngest aunts, Frances and Sophie Turner, were still alive, living in London. They had certainly communicated with the families of their colonial brothers, as we have copies of some letters. Evans is likely to have consulted with them about their families. Whether he decided that Charles was the most likely person to ask, or whether he also wrote to others, I do not know.

ES Evans finds another heir

Maybe Charles replied that none of his siblings were interested in claiming an inheritance Evans had labelled “a white elephant”. Alternatively, if the next in line really was Charles’ older half-brother John Bailey Turner, it’s possible that no one knew where he was. In any case, what happened next indicates that ES Evans decided to find a new heir.

This decision was made easier by some changes in the laws regarding the breaking of entails. Prior to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, entailing estates was a common, legally-binding method used by landowners to keep land within the family. Whether declared in a Will, a marriage settlement, or other type of deed, the instruction was that the land was to go to the eldest son for life and then the remainder to pass to his son’s eldest son “in fee tail” (in tail/entailed) and on to their issue. This had the benefit of keeping the property intact (rather than dividing it into smaller and smaller parcels). It also prevented spendthrift and frivolous heirs from selling the land to fund their gambling, debts, or other bad habits, and thus using up the next generation’s inheritance. But there were some serious disadvantages, including the inability to sell the property when it had become uneconomic to run. Sometimes they could not use the land in certain ways that could be considered a “waste” of the resources on that land. This meant that the landowner could not increase their income off the land in new ways. Another problem was that deeds and Wills often included a widow’s annuity and “portions” for the younger children/daughters. These could run to the thousands of pounds, and had to be raised from the profits of the land. It was feasible that the sum given to the widow or younger children would use up the larger part of the income derived from the land, leaving insufficient income for the tenant-for-life, let alone pay for the upkeep of houses and farms.

The Settled Lands Acts of 1882 and 1890 addressed this situation by giving the tenant-for-life greater powers to deal with the property than had previously existed.[17] This meant that Commander Evans was now able to settle Whiddon Park on someone else. In 1912 he signed indentures which reflected his intent that after his death, Whiddon Park would be put in trust for the benefit of his godson, Edward Arthur Craig Fulton. During Mr Fulton’s lifetime and at his request, or after his death, the trustees could sell Whiddon Park, or any part of it. The proceeds of such a sale would be invested for Mr Fulton’s benefit. Mr Fulton could leave the trust to anyone in his Will, and if there was no Will, the trust would be settled upon his children. Commander Evans’ Will also reflected this arrangement. When Evans died on the 20 March 1920, Whiddon Park became the property of Mr Fulton.

Edward Arthur Craig Fulton

Edward Arthur Craig Rampini was born in Elgin, Scotland in 1888. His father Charles Joseph Galliari Rampini was a barrister and served as the sheriff of Elginshire, and his mother was Annie Burness. Despite the Italian name, Edward’s parents were born in Scotland.

Just how Edward Seymour Evans knew the Rampini/Fulton’s I do not know. As EAC Fulton is described as Commander Evans’ godson, he must have known the Rampini family in the 1880s. They appear to have holidayed together at least once, in 1898 when the Rampinis and Captain Evans stayed at Summerhill House in Strathpeffer, Scotland.

In the 1901 census, the Rampini family were living in Paignton, Devonshire, not far from Chagford. In 1910, Edward Rampini changed his name to Edward Fulton. It appears that his brother Frederick also changed his name to Fulton, but at this stage I have not learned the reason for this.

Edward Fulton was working as an articled clerk when he enlisted to go to World War I. He served in the 2nd London Regiment, Highland Light Infantry, attached to the 2/4th Gurkhas, from August 1914. He was stationed in Malta first, then France from 1915-1917, and India 1918-1919. He left with the rank of captain.[18]

After the war, he travelled back and forth to the US a few times. In 1922 he married Alice Aldidge in Paignton. She was of a New Orleans family. They lived in New Orleans for a few years. The couple can be found there on the 1930 US Census. It appears they divorced, and Fulton returned to England and married a second time, in 1940 in Devonshire. His second wife was Maud Georgina M. Forsdyke.

What happened to Whiddon?

As it happened, Mr Fulton did sell the property. In 1921, Whiddon Park was sold to Julius Charles Drewe for the sum of £8000. That’s equivalent today to £401,000.[19] Drewe also bought some adjoining land, where he built Drogo Castle. Since then, Whiddon House has passed on to others’ hands, and what was the enclosed deer park is now managed by the National Trust.

The contents of the property were also sold, by auction on Thursday 7th April, 1921 by Arthur Coe and Amery auctioneers. The advertisement below details a long list of furniture, carpeting, bedding, paintings, clocks, bookcases and books, a naval barometer, kitchen items and outdoor effects such as garden seats and lawnmowers.

Edward Arthur Craig Fulton died in 1968. There is no mention of a probate or Letters of Administration on the English probate calendars. It is likely that his estate passed over to his widow. Maud died the year after, in 1969 in Paignton. Her estate was probated and was valued at £10,728. As she was 49 years old when she married Edward, it is unlikely they had any children.

One last question – why was ES Evans looking for Andrew’s children?

Early on, I mentioned the curiosity that ES Evans was looking to his uncle Andrew’s family as the next in line to inherit Whiddon. Of the 10 children of Rev John and Mary Turner, only 3 had sons – Mary Evans, Andrew Cheape Turner, and Alfred Rooke Turner. During my earlier days researching the family history, everything pointed to Andrew being older than Alfred. Based on the ages they gave at the time of their marriages, and on the birth certificates of their children, it looked like Andrew was born around 1826 and Alfred in 1828. Although I don’t know why, maybe their sisters in England (the ones who Evans would have consulted) believed this too. But the reverse is true – Alfred was born first, and Andrew is the youngest of the sons.

Does this mean that Alfred’s children were really the rightful heirs? Maybe, but not if they had to prove their relationship. Today, when an intestate estate is to be distributed to the rightful heirs, especially when dealing with a large family who have spread over the globe, the relationships between the heirs and the Deceased have to be proven with birth, death and marriage certificates and other sources (such as census records, Wills, immigration records, etc.).

I do not know whether this was the standard in the 1920s. However, given how many “next of kin” agents advertised in the newspapers, offering to obtain the relevant records for heirs, I think it possible that “proof of kinship” was required.

The reason it matters in this case is that both Alfred and Andrew had common-law relationships that produced children. But in those days, children born out of wedlock were not entitled. If these “illegitimate” children of either man were required to produce a marriage certificate for their parents, they would not have been able to – and may therefore have been excluded from inheriting Whiddon.

This applies to John Baily Turner, who ES Evans was looking for. He was the son of Andrew Cheape Turner with his first wife, Harriet Hiscox. Although I’m not sure of this, it looks like JB was not raised by Andrew and his legal wife, Grace Rose. John Baily Turner disappears from the records until the early 1900s, when he is found on electoral rolls in Queensland. He died in 1920, alone. Had he been alive to try to claim Whiddon, it would not have worked, if he had to prove his parents’ marriage.

With regards to Alfred, he had a number of children with Mary Ann Eliza Lane, including sons. But he and Mary Lane were not married. Later he was to marry Margaret Devine. There are two children whose birth certificates show Alfred as their father. But the one born after the marriage died before ES Evans died, and had no surviving children. Hence, Alfred’s line legally could not claim the estate – if they had to prove themselves.

So in the end, it is probably Andrew’s line who could legally claim the estate – not John Baily Turner, but Charles and his siblings.

But alas, it was not to be, and Whiddon passed in other hands.

NOTES

[1] From White’s Devonshire Directory (1850), accessed on GENUKI https://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/DEV/Chagford

[2] Hayter-Hames, Jane. A History of Chagford, Chagford, Devon: Phillimore. (1981).

[3] For a full description, see https://heritagerecords.nationaltrust.org.uk/HBSMR/MonRecord.aspx?uid=MNA151566; Hayter- Hames, p. 60; “Whiddon Park House, Castle Drogo; Devon and Cornwall” National Trust, https://heritagerecords.nationaltrust.org.uk/HBSMR/MonRecord.aspx?uid=MNA151566

[4] Greeves, L. 2004. History and Landscape – A Guide to National Trust Properties. London: National Trust Enterprises Ltd.

[5] Whitaker, J. 1892. A Descriptive List of the Deer Parks and Paddocks of England. London: Ballatyne & Hanson.

[6] Greeves, L. 2004. History and Landscape – A Guide to National Trust Properties. London: National Trust Enterprises Ltd.

[7] Polwhele, 1793, quoted on the website Legendary Dartmoor, https://www.legendarydartmoor.co.uk/whiddon_park.htm, though it does not provide the exact citation. Polwhele published two books in 1793, Historical Views of Devonshire and The History of Devonshire (in 3 vols published 1793–1806) (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Polwhele).

[8] Murray, John. A Handbook for Travellers in Devon and Cornwall, London: Spottiswoodes & Shaw. (1851). quoted on the Legendary Dartmoor website (https://www.legendarydartmoor.co.uk/whiddon_park.htm)

[9] Hayter-Hames, Jane. A History of Chagford, Chagford, Devon: Phillimore. (1981).

[10] May refer to a card game, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Put_(card_game)

[11] “Currency Converter: 1270-2017,” The National Archives, https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter/#, accessed 9 Jan 2022.

[12] “Married Women’s Property Act 1882,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Married_Women%27s_Property_Act_1882, accessed 2 Nov 2021 (page last edited 25 Oct 2021).

[13] See the documents DD/FS/41 held at the Somerset Heritage Centre. I have obtained digitized copies of many of the items held in this collection.

[14] Letter from Mr Broderip to Mr Senior, undated; Somerset Archive, DD/FS 40/8/2

[15] Letter dated 22 Mar 1833 Somerset Archive, DD/FS 40/8/2

[16] Exeter Flying Post 20 Sep 1869. Note also that on the 1851 Census, there is an entry for George Webber and family at Whiddon House, and a separate entry for Mary Jane Turner and her children also at Whiddon House.

[17] From Wikipedia entry on Settled Lands Act of 1882 and 1890

[18] Record of Service of Solicitors and Articled Clerks with His Majesty’s Forces 1914 -1919; Spottiswoode, Ballantyne & Co. Ltd., London, 1920; accessed at https://archive.org/stream/recordofserviceo00soli/recordofserviceo00soli_djvu.txt

[19] CPI Inflation Calculator, https://www.officialdata.org/uk/inflation/1921?amount=8000, accessed 2 Nov 2021.